History is full of hilariously misattributed names. French fries didn’t come from France (fun fact: it’s actually from Belgium!), English muffins were invented in the US, not in Britain, and Scotch tape is most definitely not a Scotland native.

But Spain drew the short straw: out of all the things that could’ve been named after your country, they got stuck with the flu. Yep, the “Spanish flu”—or sometimes called the “Spanish lady”— that caused the infamous 1918 influenza pandemic didn’t originate in Spain, but at a military camp in the United States.

All jokes aside, the flu outbreak in 1918 was one of the worst pandemics yet. It killed more people than both World Wars combined, yet it rarely gets the same spotlight as the Black Death or even COVID-19.

So, today, we’re giving it overdue attention and examining how a simple flu reshaped history.

But before we go any further, here’s a quick vocab check so we’re all on the same page:

Epidemic → A disease that spreads rapidly in one region (local problem).

Pandemic → A disease that doesn’t respect borders and goes global (hello, COVID).

Endemic → A disease that sticks around in a place, with predictable levels of occurrence (chicken pox, malaria).

Table of Contents

- Origins of the Pandemic (Early 1918)

- Well, What Exactly Was the Spanish Flu?

- So, What Made the Spanish Flu That Deadly?

- Lasting Legacy: The “Forgotten” Pandemic of 1918

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Origins of the Pandemic (Early 1918)

There were a lot of claims about where exactly this disease originated. Some medical scholars pointed fingers at the pulmonary disease that broke out in China, while others argue it was from a “purulent bronchitis” (an inflammation of the airways/bronchi where the mucus produced in the lungs contains pus) that devastated a British Army stationed in France.

But the widely supported hypothesis about this pandemic’s origin was at a military base at Camp Funston, Kansas, in March of 1918.[1] Cramped quarters and poor sanitation created the perfect environment for the virus to spread, and within a week, it hospitalized 522 soldiers with severe influenza.[2]

As if that wasn’t enough, the timing was as bad as it gets. With World War I raging, constant troop movements became a catalyst for the spread of the virus.

In less than a month, officials across Europe were already reporting cases. This was how Spain got its bad rep.

Both the Allies (the UK, US, Soviet Union, and China) and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria) suffered massive losses from the Spanish flu, but they suppressed reports to prevent the enemy from gaining potentially useful information.

As a neutral power, however, Spain had a free press that openly reported on the mounting death toll. Worldwide media quickly caught up with this news, creating a false impression that Spain was the epicenter of the disease. Thus, the misnomer “Spanish flu” was born.[3]

Well, What Exactly Was the Spanish Flu?

Let’s talk medical terms.

The H1N1 virus caused the strain of influenza known as the Spanish flu. Initial symptoms included fever, dry cough, sore throat, head and body aches, and loss of appetite. But these quickly escalated to more severe ones, such as pneumonia and skin turning blue from the lack of oxygen (rapid cyanosis).

Unlike typical seasonal flu outbreaks, which tend to hit the very young and very old hardest, this pandemic struck a surprising demographic: healthy young adults in their 20s and 30s.

Scholars noted that,

“These infections in humans are accompanied by an aggressive pro-inflammatory response and insufficient control of an anti-inflammatory response.”[4]

In short, the ‘Spanish lady’ had severe effects on adults in their prime precisely because their immune systems were strong and capable of mounting a very aggressive defense. But in this case, that strength backfired: their bodies overfought the virus, unleashing massive inflammation (the “cytokine storm”) that damaged their lungs and organs.

Talk about tragic irony.

So, What Made the Spanish Flu That Deadly?

The 1918 influenza was especially alarming because of its speed and scale. The virus spread across continents in mere months, infecting an estimated one-third of the world’s population. With the three waves of the pandemic, about 50-100 million of them died.

At the time, medical science had limited tools to fight it; antibiotics didn’t exist yet, vaccines weren’t available, and even basic knowledge of viruses was in its infancy. Doctors didn’t even realize a virus caused influenza. The best they could do was to take preventive measures, such as supportive care and isolation.[5]

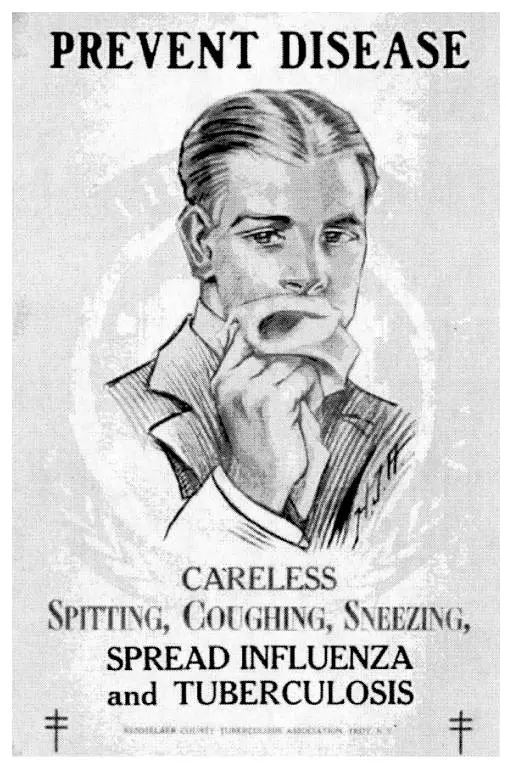

As the death toll mounted, desperate measures followed. In the US, authorities enforced anti-spitting ordinances, closed schools and entertainment venues, and required people to wear masks and use handkerchiefs or disposable tissues when coughing or sneezing, all to prevent the spread of the virus.[6]

Pretty much like what we’ve all experienced during COVID, except that this happened a century ago.

Lasting Legacy: The “Forgotten” Pandemic of 1918

If the 1918 pandemic was so catastrophic, why isn’t it more widely remembered? The primary reason was that it was overshadowed by the Allies’ victory during World War I.[7] Apart from this, no one really wanted to talk about what it was like to live through such a disaster. The events traumatized doctors, and only a few personal stories appeared in print.[8]

Regardless, its devastating impact shaped public health policies for decades to come. Since 1918, medical science has made major breakthroughs that later helped the world confront COVID in 2019.

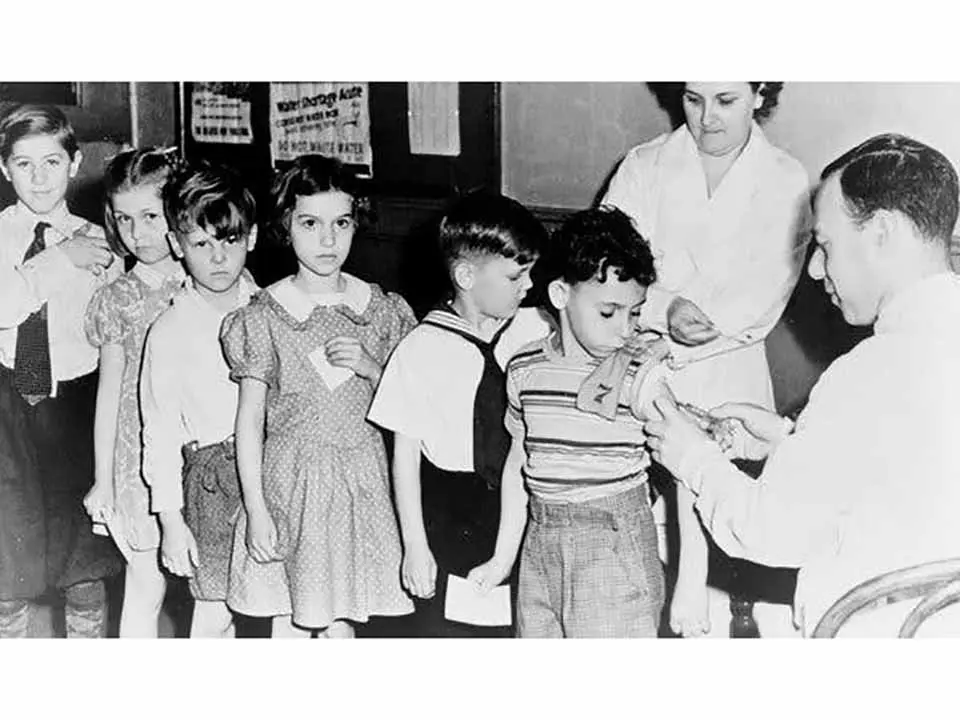

In 1945, scientists at the University of Michigan introduced the first flu vaccine to the public. Since then, research has advanced, with new vaccine technologies continuing to emerge today.[9]

Governments across the world also began multilateral efforts in controlling pandemics. The first International Sanitary Convention in 1926 set out regulations for handling communicable diseases. After World War II, the United Nations established the World Health Organization to “promote health, keep the world safe, and serve the vulnerable.”

The first International Sanitary Convention was held in 1926, where provisions and regulations on how to handle communicable diseases were discussed. After the Second World War and the establishment of the United Nations, the World Health Organization was also created with the goal “to promote health, keep the world safe, and serve the vulnerable.”[10]

Clearly, the echoes of the 1918 influenza are far from forgotten. While details may blur with time, its legacy endures—in the way we respond to outbreaks and in the systems we build to protect public health.

And no, we shouldn’t view a pandemic of this magnitude as merely a scar in history, but as a reminder of humanity’s fragility and resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What caused the Spanish flu?

The Spanish flu was caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus, which spread rapidly in 1918 due to overcrowded conditions during World War I and a lack of effective treatments or vaccines at the time.

Does the Spanish flu still exist?

The exact 1918 strain no longer circulates, but descendants of the H1N1 virus still exist today. In fact, the 2009 “swine flu” pandemic was caused by a strain related to the 1918 virus.[11]

What is the deadliest pandemic in history?

The Black Death of the 14th century remains the deadliest, killing an estimated 75–200 million people. However, the Spanish flu is one of the deadliest of modern times, with 50 million deaths worldwide.

Is there a cure for Spanish flu?

There was no cure in 1918, which is why it spread so devastatingly. Today, antiviral medications like Oseltamivir (Tamiflu®), vaccines, antibiotics for secondary infections, and advanced medical care would make it far more manageable.[12]

References:

[1] The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications – PMC

[2] Purple Death: The Great Flu of 1918 – PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization

[3] Why Was It Called the ‘Spanish Flu?’ | HISTORY

[4] The influenza of 1918: Evolutionary perspectives in a historical context – PMC

[5] The Spanish flu – ScienceDirect

[6] When Mask-Wearing Rules in the 1918 Pandemic Faced Resistance | HISTORY

[7] Why historians ignored the Spanish flu

[8] Why the 1918 Flu Became ‘America’s Forgotten Pandemic’ | HISTORY

[9] History of influenza vaccination

[10] What we do – World Health Organization

[11] The 1918 Influenza Pandemic and Its Legacy – PMC

[12] Reconstruction of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic Virus | CDC

0 Comments